Overcoming the "syllabus gap" at work

Rethinking how we design career-connected learning experiences

👋 Heya, thanks for reading. ☀️ Happy graduation and start of summer for many of you! 🎓

I’m writing because education wasn't designed around students but we can improve the learner experience through design. I share stories, tips, and work in progress weekly.

Why it matters: Higher ed efforts to prepare students for careers often rely on surface-level fixes—internship courses, classroom projects, and plug-and-play platforms—without addressing the root challenge: systems aren’t designed for shared value between students, faculty, and employers. Designing for real change means building scalable, relationship-driven, and work-integrated learning experiences that align incentives and deepen impact. Here’s what I’m learning from my recent work and how design is helping to make meaning and build a way forward.

Go deeper:

“Student’s don’t know how to transfer what they’re learning in class to resumes, interviews, or their job experience” -Employer

“Working on bringing professional skills into the curriculum, but constantly being ask to put more into courses, and how do we do both [content and professional skills]?” - Faculty

“In upper level courses we have projects, capstone courses, but they are resource intensive and they are hard to pull off.” - Faculty

“College can be black and white, of, like, I have to do this, this, and this. To get a job, or I have to do this, this, and this to get an A in the class. And then people come to work, and there's a lot of gray area […] students really struggle with ambiguity.” -Employer

After interviews with faculty, design workshops with employers for my career readiness project at a partner business school in Minneapolis/St. Paul, review of 20+ applications for a national design cohort for colleges and universities focused on the intersection of learning and work, and a brunch with friends who are managers of new grads on my recent trip to DC, these insights are surfacing over and over.

Everyone seems to feel held back by the systems that exist today limiting high value work-integrated learning.

Faculty feel the tension of making the curriculum relevant and offering career preparation in the margins alongside ensuring that individual course objectives are met.

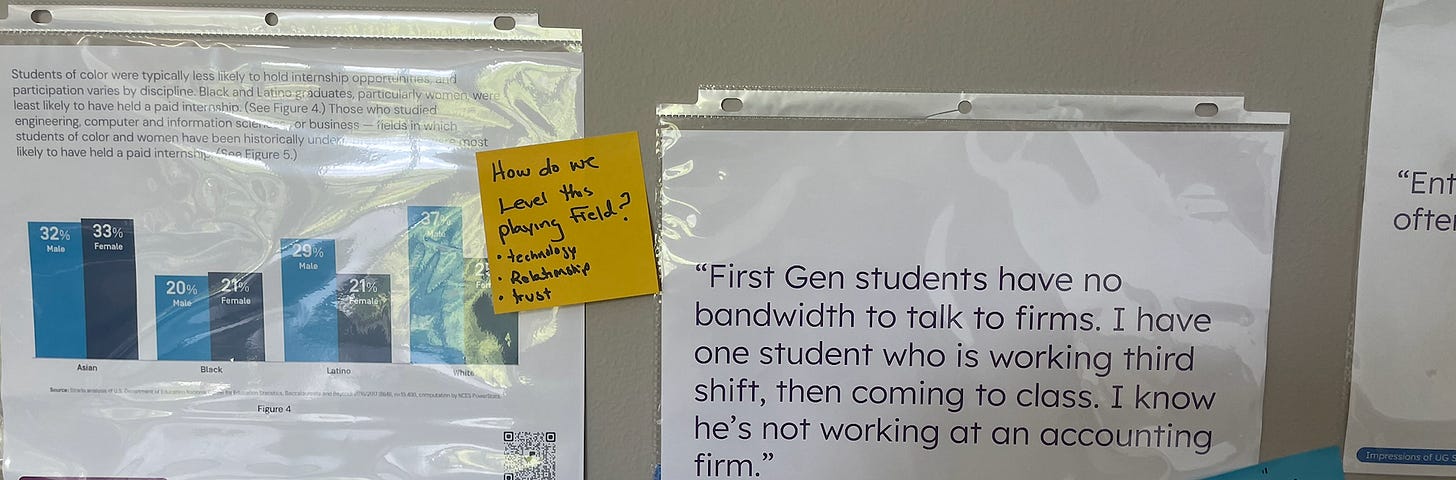

Staff see the difficulty to engage students outside of the classroom, especially first-gen and “new majority” learners, because of their other work, home, and personal commitments that keep traditional “college” at arms-length.

Administrators see the limited resources across campus to build the necessary infrastructure to support student and career success at scale.

Employers want to see students with experience to de-risk their hiring and maximize early productivity but feel the gaps in school to work translation, especially the “syllabus gap,” or student challenges that result from lots of structure and guidance in academic settings that often doesn’t exist at work.

But many seem lost about what to do, or get stuck in old patterns of systems and solutions that don’t address needs and align incentives.

Common practices often feel like solving the problem on the surface, but don’t always solve against the core problems.

Practice 1: Internship Courses

The conclusion that many arrive at is the need for credited internship experiences that can bring work into the curriculum or in-class projects as community-engagement or capstones.

But the unfortunate reality of these sometimes under-designed and superfluous degree credits, or worse, the fact that students pay to take these internship “courses” rather than get paid for their work-based learning.

That’s not all. Even thoughtfully designed, curriculum-driven internships can’t solve the larger problem: “There were 8.2 million college students who wanted an internship last year. Only 3.6 million got one, and of those, only 2.5 million had what they called a quality experience in that internship.” (Brandon Busteed, Work Forces Podcast)

But colleges and universities know they need to prepare students for careers, so their efforts don’t stop there.

Practice 2: Class Projects for Applied Learning

This often means in-class projects become the next best way for employer-connected efforts. And project-based learning often falls to proactive and highly engaged faculty to individually pursue local employer partnerships, scope projects, manage stakeholders, and coach students along towards successful outcomes while trying to integrate other key course concepts. And it’s a lot to ask to also consider how to integrate skill development and reflection into the course design.

Practice 3: Tech-Enabled Employer Relationships

Increasingly, the lack of infrastructure to collect, scope, and manage projects leads institutions to pursue platforms that facilitate connections to this kind of learning through national employers, simulations, or co-curricular projects on their behalf. Which is great for offering the experiences, but often doesn’t meet University and student needs to build partnerships and networks that can lead to jobs.

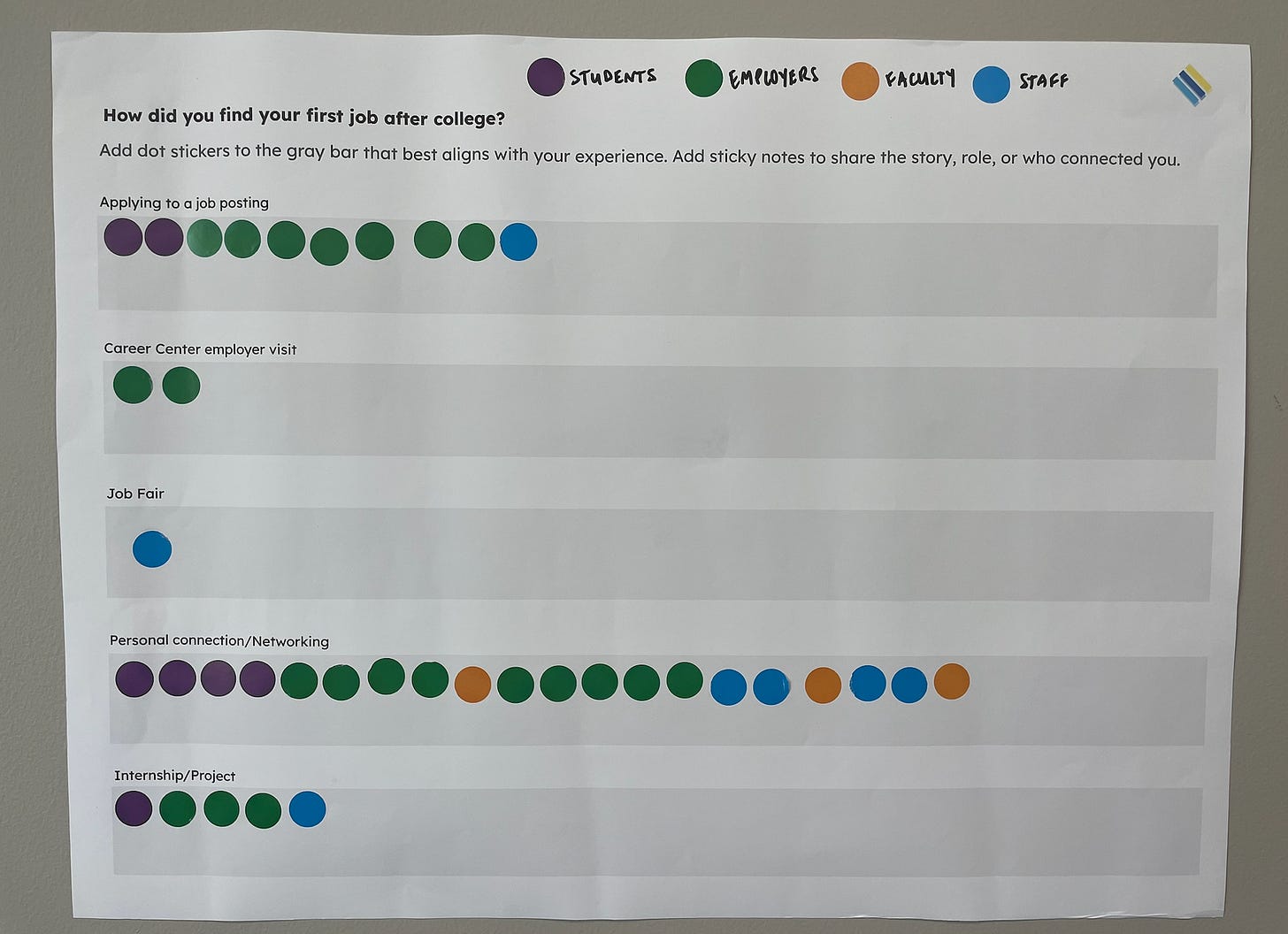

What this approach misses is the strategic relationship development with local employers to engage with partnership in mind rather than transactional, short-term, relationship-driven commitments. Individual connections at employers (or alumni) often work with a single faculty member in a single class to work on a real problem for one class section of students.

Of course Universities, career centers, family and business centers and community engagement departments want to build these relationships for the institution, but students benefit as well. This exercise during a recent set of design sessions left a powerful reminder as we develop programs: jobs come from relationships.

Criteria for Successful Career Preparation Concepts

Concepts or approaches are ways of addressing the identified needs through potential “solutions.” Sometimes before identifying potential solutions, creating design criteria (or outlining what a solution must do) is a helpful guide in identifying promising ways of solving the problem as they’re grounded in the needs and insights that you identify. Here are a few criteria synthesized from the learnings above:

Concepts expand scope and deepen relationships between Employers, Students, and Universities from transactional to collaborative and strategic

Concepts blur traditional ways of student’s experience with learning and work to more deliberately create contexts for seeing work as learning and learning as context for work

Concepts are scalable and accessible to students with limited time or commitments beyond their education

Concepts enable faculty to integrate career-relevant work into their class by simplifying scoping and partnership development

Concepts maximize relationships and establish a clear ‘tier’ of engagement that offer insight into more episodic and more strategic partnerships

With these criteria in mind, I thought it might be helpful to see some concept provocations that bring them to life.

Concept Provocations that Meet Stakeholder Needs

Concept 1: Employer Investment in Student Futures

What would it look like to start a scholarship fund for local employers to invest in these kinds of experiences for students that not only covers student tuition, but offers stipends at the successful completion of key course milestones? I’d bet employers would be more strategic about their engagement with students in internships, and it would offer a model for partnership over bespoke engagement. It might even make efforts for funding easier as employers could route internship support through corporate social responsibility efforts and receive the brand lift for investing in student scholarships.

Concept 2: Place-Making of Learn and Work Onsite

What would it look like to blur the physical spaces and activities of learning and work by allowing students to attend virtual or hybrid classes onsite at local employers during days working onsite, or to work remotely from campus after class? What if one on ones with internship managers included questions about what students are learning and classes deliberately surfaced challenges and questions from student work experiences as they applied to class topics and exercises?

Concept 3: Growing Strategic Relationships through Alumni Career Engagement

If projects come in through individual employer connections, why not start with Alumni? Match Alumni in relevant industries with professors teaching multiple sections of the same course and consider a common project for all or a few sections. Imagine a project “flywheel” expanding local alumni partnerships into their companies and company partnerships into strategic project competitions across multiple course sections at once involving volunteer support from alumni as mentors, judges, and project leads in exchange for real work outputs on a real company project (or broad problem space) and lead to internships or other more deeply integrated follow-up experiences for students (meetings with senior leaders, access to exclusive events, etc).

Through engagement with an alumni network at the company the relationship grows through individuals, but can build by considering what might be exchanged for volunteer time. Employers might be interested in exchanging these kinds of experiences for continuing education for their managers or leaders or a discounted programmatic offering that develops their team.

A disclaimer before you start “doing”

These are by no means perfect or all encompassing, but they hopefully open your mind to realize the importance of identifying the qualities of the problems you’re working on and the criteria that solutions must meet to solve a problem. These concepts are meant to bring the process to life.

With any concept that you develop, before moving forward it’s important to surface the assumptions that are embedded in that concept, prioritize them, and test them deliberately to build confidence that you’re meeting stakeholder needs.

Insights from the Field

Bringing you voices from across education to answer:

What advice would you give to someone driving change in education?

“Make it a habit always to take a step back, pause, and ask yourself (and your colleagues): What problem are we trying to solve? This simple question will lead you to something important: understanding the "system" you're working in and what about it needs to change.

This approach has been well-documented in recent years by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, and I like it because it flips the script on how most higher education leaders think about change. Instead of jumping in with ideas about what's broken or what you want to fix (and falling into what I call "the solution trap"), step back and look at what's actually happening around you.

Ask yourself: what's going on here, really? What results is this place getting right now? Why do the same outcomes keep showing up year after year? What daily routines, unspoken rules, and ways of working create these patterns?

When you start here, you'll discover the real reasons why change may be necessary. You'll better understand the hidden processes and relationships that shape the problem. Think of yourself as a detective, uncovering why things work the way they do. Only then can you figure out what actually needs to change. This approach also prevents the common mistake of adopting solutions that miss the real problem, and will help you ensure you focus your efforts on what will truly make a difference for your learners and your organization.“

Brian Fleming, Author, The Solution Trap: When Learning Innovation Fails, And What To Do About It

Learning is better when it’s social.

If this post moved something in you, tap the ❤️, pass it along, or join the conversation on LinkedIn—I’d love to hear what it sparked.